or "Telling of the great things that the Lord has done for Us…"

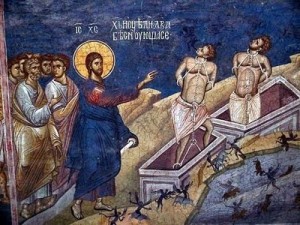

The last couple of weeks have provided me with an opportunity to think again on the dangers of being controlled by the crowd, of being conformed to the spirits of our age rather than allowing our minds to be transformed by the working of the Holy Spirit. Two weeks ago in the “new” Orthodox liturgical calendar we read Luke’s version of Jesus’ encounter with the demoniac who was possessed by Legion, so called because the forces that were driving this poor man were many. The appearance of this reading in the lectionary was providential, as it reminded me of the readings offered by René Girard and adapted to a gay audience by theologian James Alison.

The last couple of weeks have provided me with an opportunity to think again on the dangers of being controlled by the crowd, of being conformed to the spirits of our age rather than allowing our minds to be transformed by the working of the Holy Spirit. Two weeks ago in the “new” Orthodox liturgical calendar we read Luke’s version of Jesus’ encounter with the demoniac who was possessed by Legion, so called because the forces that were driving this poor man were many. The appearance of this reading in the lectionary was providential, as it reminded me of the readings offered by René Girard and adapted to a gay audience by theologian James Alison.

As my parish priest commented on this story, he noted the incredulity with which modern people look on stories of demonic possession. We have largely substituted explanations from psychology and biochemistry for older explanations of strange and destructive behavior. But inwardly I smiled as he attempted to move the sermon onto more comfortable ground. I know what it’s like to be run by a crowd who attempt to shape the demoniac’s narrative, who drive the object of their derision toward acts of self-destruction.

Girard is no metaphysician. His explanation of the demoniac brackets supernatural forces to examine the anthropological elements of the gospel’s account. A member of a group, chosen by his whole town, is driven out and bound in chains. Though he bursts the initial bonds that hold him, he continues to run naked among the tombs, hurting himself. The demoniac has internalized the narrative of his community. He believes that he is bad, that he deserves exile, and as long as he stays away, the rest of the community lives at peace. Alison adds a new layer to the story. He and his audience are all too familiar with the self-destructive habits that often trap gay individuals, and the reactions from their communities:

The very fact of the evil acting-out reinforces our adherence to the belief structure offered by the group: the group can explain it, make it seem tolerable, even forgive it on occasion, because it actually contributes to making what they claim to be good appear to be, in fact, good. If you only know being gay as a series of sordid, furtive, highly-sexualized sorties from "normal life," where you are constantly ambushed by guilt, then you will consent to the group definition, and agree with them that since this is what being gay is all about, the group’s portrayal of it as the dark side of normal life is right. A bit of will-power and all will be OK. Perhaps this is why so many closeted gay people in religious organizations are so prone to persecuting other gay people, because their goodness, and hence their belonging, depend on their having agreed to displace, and expel as evil, part of their being, an expulsion which needs constant reinforcement, a sacrifice which needs constant repetition (Alison, 129).

Alison goes on to note that we demoniacs learn to act out in ways that are harmless to the group that defines us, taking out our destructive impulses on ourselves. But in the Gospel account, Jesus disrupts this unconscious pact between the demoniac and his community. Rather than buying into the narrative and leaving him alone as the demoniac requests, Jesus looks at the man and exorcises his demons, calling this poor soul into relationship with him. Ever so gently he begins the process of providing a new identity, one rooted in relationship with Christ.

Alison goes on to note that we demoniacs learn to act out in ways that are harmless to the group that defines us, taking out our destructive impulses on ourselves. But in the Gospel account, Jesus disrupts this unconscious pact between the demoniac and his community. Rather than buying into the narrative and leaving him alone as the demoniac requests, Jesus looks at the man and exorcises his demons, calling this poor soul into relationship with him. Ever so gently he begins the process of providing a new identity, one rooted in relationship with Christ.

When the townspeople see what Jesus has done, they are afraid. They ask Jesus to leave! As long as there is a demoniac that they can label as bad, they are safely in the opposite category, able to call themselves good. But the formerly possessed man is now "clothed and in his right mind," and his transformation upsets the system the townspeople have created to define their own self-worth.

The demoniac wants to leave with Jesus. But Alison points out that this would come much too close to looking like expulsion from the community. It would be indistinguishable from the normal scapegoating mechanism by which we unconsciously pick out the one who symbolizes all the ills of our group, pour our contempt and scorn on this accursed one, and drive the evil-doer out. (In archaic societies, Girard notes that we used to kill our scapegoats. This still happens in some situations, where a unanimous group finds them guilty of crimes deserving death. But in the Western world, those instances are fewer than they used to be.)

Instead of taking the man away from his community, Jesus gives him another task: go and tell of all the good things that the Lord has done for you. This can be a very hard task. The crowd certainly doesn’t want to hear it. And their reaction is often dismissive or cruel. Sometimes they might even drive the one away who no longer serves in the role they have previously assigned. But this is the way that God often works, by leaving the person who has received healing in the midst of the group as a witness to the power of God.

Hearing this story again during church proved to be providential preparation for the events that unfolded shortly thereafter. Only one day before, Fr. Robert Arida had published an essay on the "Wonder" blog, a resource provided by the Orthodox Church in America for young people.

In his essay, Fr. Arida challenged the common misconception that the Holy Fathers of the Church have provided ready-made answers for all the questions asked in modern society and the accompanying claim that the Patristic sources are unified in their theological opinions and beyond critique. In the end of his essay he suggested that the Church should not be afraid to engage with the questions of contemporary culture—real questions around issues of "human sexuality, the configuration of the family, the beginning and ending of human life, the economy and the care and utilization of the environment including the care, dignity and quality of all human life" (Arida, 4). The ensuing firestorm took a few days to spark and burn through the Internet, and has been well documented elsewhere (for example, Eric Simpson’s excellent overview).

But what has me writing today is a secondary reaction. As with many skirmishes in the ongoing culture wars, I find myself assailed by new pronouncements of the same old rhetoric. Again and again we hear about the proverbial camel’s nose that has managed to get under the tent, about the detrimental effects that open discussion will have on impressionable youth, about the lavender mafia that seeks to undermine the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. The new blog posts come with a healthy dose of mischaracterization, describing me and other LGBTQ folk as people subject to disordered passions and demonic oppression. We are to be mercilessly driven out of the church. Anyone seen as supporting us is invited to leave Orthodoxy to become an Episcopalian. The mechanism that defines the righteous "us" over and against the sinful "them" is hard at work.

While I haven’t gone out of my way to look for reactions to Fr. Arida’s essay, my own circle of acquaintances, also on the receiving end of much of the polemical rhetoric and decidedly unpastoral responses, posts links to each new response. As a scholar of religion and of gender and queer theory, I dutifully clip these responses and file them away for later study from a more objective remove, perhaps for some future article.

But more troubling still is the desire to go back and dig up past examples of these posts. The Orthodox blogosphere is littered throughout with anti-gay, anti-feminist, anti-modernity posts. (Had the Internet been my only source of information, I would never have embraced Orthodoxy myself.) And for some of my fellow Orthodox, there is a perceived need to go out and dig these posts up, to breathe new life into them, and to post them all over again. Even when we’re no longer chained to the rocks, we still act out our roles, cutting our own flesh and throwing ourselves on the fires kindled by our enemies. We needn’t be in direct contact with them. We’re good at carrying out their punishments all by ourselves. As we collectively pick at our wounds and tell stories of our oppressors, we unconsciously reverse the dynamic. We are good because they are bad. Jesus is with us because we are being oppressed by them. (Note: This is not to blame the victims. It is the impulse to join in keeping things stirred up that I am critiquing, rather than the individuals who succumb to the voices that command them to do so.)

The reminder of Jesus’ encounter with the demoniac came just in time. Jesus respectfully withdrew when the townspeople asked. He didn’t take the demoniac with him. He simply freed him from the Legion of voices that sought to run his life. And Jesus gave him a new task: to declare all the good things that the Lord had done for him. There’s a certain logic in this. It is very hard to continue to engage in negative behaviors and relive the hurts suffered at the hands of the mob when one is busy declaring the praises of Christ who has saved us and given us new life.

As the noise continues, coming from both the "good" crowd that derives its identity by not being "one of those" and also my fellow demoniacs who are still enthralled to the voices they have internalized and act out, I can only look to Christ. It is Christ who greets us, rescues us, drives out the other voices, provides us with a new identity within his Body, and commands us to tell of the good things he has done for us. It is only through this dynamic, keeping our eyes on him, that we can stand calmly in the midst of the tempest.

As the noise continues, coming from both the "good" crowd that derives its identity by not being "one of those" and also my fellow demoniacs who are still enthralled to the voices they have internalized and act out, I can only look to Christ. It is Christ who greets us, rescues us, drives out the other voices, provides us with a new identity within his Body, and commands us to tell of the good things he has done for us. It is only through this dynamic, keeping our eyes on him, that we can stand calmly in the midst of the tempest.

Girard tells us that human beings are fundamentally imitators of those around them. Contrary to the entire Enlightenment project, we are not self-made individuals who set our own rules, our own goals, our own desires. We are driven by the desires that we see around us. And it is the Holy Spirit that breaks through the crowd, offering us a vision of God that defies the mob, calling us to the imitation of Christ.

To imitate the voices of the age (and they are Legion) or to imitate the example of Christ: these are the options laid out before us. As the culture wars continue, I encourage us all to continue to look on Christ, to tell of all he has done for us, and to live into his call.

Further Reading:

Luke 8:26-39. The Gospel reading for November 2, 2014.

Girard, René. "The Demons of Gerasa." In The Scapegoat. Translated by Yvonne Freccero. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Alison, James. "Clothed and in His Right Mind." In Faith Beyond Resentment: Fragments Catholic and Gay. New York: Crossroad Publishing, 2001.

Arida, Robert M., "Never Changing Gospel; Ever Changing Culture." On Holy Trinity Orthodox Cathedral. http://holytrinityorthodox.org/articles_and_talks/Never%20Changing%20Gospel.pdf (accessed November 7, 2014).

Simpson, Eric. "Why Wonder When You Already Have All The Answers?" On Marginal Accretion. http://marginalaccretion.tumblr.com/post/102114173805/why-wonder-when-you-have-all-the-answers (accessed November 9, 2014).

And for those seeking a meditation:

Badham, Raymond Joel and Martin W Sampson. "In Your Freedom." From the album Savior King. Sydney: Hillsong Music Australia, 2007. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2AZPUigI0Nc (accessed November 14, 2014).

Crocker, Matthew Philip and Joel Timothy Houston. "Mountain." From the album Zion (Deluxe Edition). Sydney: Hillsong United, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLSHKhgvbys (accessed November 14, 2014). (This version will have to do until the version from No Other Name makes its way onto the Internet.)

Well written and stated. ‘And when you have done all stand with your loins gird about with truth’ Stand firm Son.

As a result of the Fall we are ALL corrupt, without exception.

Some of us have a proclivity to abuse alcohol, to overeat (gluttony), and some have the disordered passion of same sex attraction. I have no idea how difficult that must be.

But every orthodox christian is called to struggle against our particular sins – and there are no exceptions for alcoholics or gays. If we struggle to obey we can expect the mercy of christ no matter how many times we fall. If we swallow the lie that god made us the way we are, passions and all, we will lose our souls.

May christ our god bless you and strengthen you as you struggle with your own passions, and may he preserve you blameless against that day.