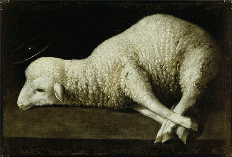

Now that I’ve had a break from school for a couple of months, I think it’s time to reflect on some of the things that nudged me toward the seminary in the first place. Atonement immediately springs to mind.

I was raised in a tradition that claimed Jesus died to pay for our sins. I’d never questioned substitutionary atonement or the penalty that Christ had paid at Calvary. In a world of tit-for-tat justice, this just made sense.

Jesus had cried out from the cross, "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" because God had turned away from the one who bore the sins of the world. It seemed only natural – God could not look on sin, and Christ had become sin for the sake of fallen humanity. A song in my childhood had said, "God turned his face from that small, lonely hill…"

It was 2005 when I was reading Chris Glaser’s Coming Out as Sacrament.[1] In his chapter entitled "God and Violence," I came across these words as he discussed ancient sacrificial rituals and the presence of God:

I do believe that when our ancient ancestors experienced the presence of God in the shedding of blood of either a human or an animal sacrifice, they were on to something. I believe that God was there, but not for the reasons they supposed. (I am aware of my presumption of their reasons.) I believe that God was there not because God delighted in this method of giving thanks, not even because God delighted that human beings were channeling their violence ritually rather than randomly, but because God was there between the severed pieces of the broken animal trying to bring those pieces back together, to heal the breach, to reconcile the parts, to stop the sacred flow of vitality that we call blood. God was there, willing at-one-ment for what human beings separated; God was there choosing life for the sacrificial victim (p. 39).

The effect was immediate. Something deep within me shifted as these words pulled back the veil from the God who hovered over brokenness, seeking to restore it. The jealous God, who smote all his enemies, was overtaken by the God of love and compassion.

I had sensed this God in the quiet, but thought him one side of the coin. Yet now this dualism was melting away and all that was left was love. The two-faced God of blessings and curses was no longer tenable… and I was in trouble.

At first I had felt reassurance. But then nausea welled up in the pit of my stomach as the implications of this "good news" swept over me: I had lost faith in what I had been taught. Belief in this God of love separated me from my heritage, my friends, and the only Christian family that I had ever known.

In an instant I had become one of those deluded people who deny the wrathful God. But compelled by what I knew deep within, I could not renounce my heresy.

For weeks after I struggled with this revelation. And in desperation, I traveled two hours to meet a friend in a parking lot in Chambersburg, PA, to confess my folly and seek advice. Spreading a blanket by some fall honeysuckle at the edge of the Food Lion parking lot, we sat under a street lamp until late into the evening as I told of what had happened, and confessed that I had lost my way.

But to my surprise, my friend did not condemn me or even contradict what I had discovered. Instead, he affirmed this revelation. For he, too, knew this God of love. And with this affirmation, I was strengthened to embrace this God of wholeness whose love is striving to reconcile the world.

Links

Reasons I went to seminary – Part 2

Atonement in 2005 Life Lessons

Atonement in the Thought of Anselm of Canterbury and René Girard

[1] Chris Glaser. Coming Out as Sacrament (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1998), 39.

I find it strangely coincidental that I spent roughly 5 hours reading today, and fully half of a three-hour-long NT lecture, on this exact same topic. In both cases, substitutionary atonement was taken to task. It ended with a reading of the hymn "At the cross" by Isaac Watts and I don’t believe I can look at it the same way again.

Working at a seminary when one is not a theologian can be: a. annoying, and b. very interesting. I have no idea what I was taught about atonement, if anything. When I became old enough to think about it I came to regard the crucifixion as a slap upside humanity’s head. More of a "See how much I love you that I would even do this" than a "In this death is the death of all your sins." Nope. Not a theologian.

Atonement has been, forgive the pun, a stumbling block for my faith as well. As a first semester seminarian, I was ready to simply do away with thinking that atonement could be part of how I saw the world, Christ, or God. However, three years later, I have come to believe it is not God who requires atonement; it is we humans. When I walk the hospital corridors seeing blood sacrifices ranging from gun shot wounds to still born fetuses, I have seen the presence of God in the midst of the suffering. Ever present. Ever compassionate.